“Exploring human stories against the backdrop of science has consistently reminded me of the value in leaving my intellectual, artistic, and narrative comfort zones to put my mind in the most personally unlikely places.”

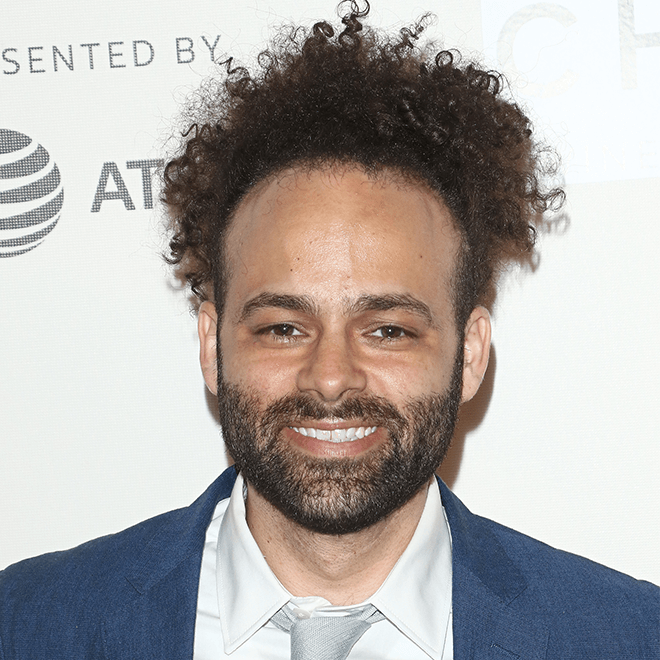

Shawn Snyder is an assistant professor at the Rutgers Filmmaking Center and an award-winning filmmaker. In 2016, Snyder was named one of Filmmaker Magazine’s “25 New Faces of Independent Film.” To Dust, his first feature, co-written by Jason Begue and starring Matthew Broderick and Géza Röhrig, premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival in 2018, winning both the Narrative Audience Award and Best New Director for Snyder. The film was released theatrically in 2019 and went on to earn a nomination for Best Screenplay at the 2020 Independent Spirit Awards.

What is your research all about? Why is it important?

I’m a filmmaker—a writer and director. At the more macro level, my interests and curiosities sit at an intersection between the personal, the intellectual, the emotional, and the spiritual—alongside a tonal and structural playfulness and a desire to passionately engage with genre and various movements throughout film history. For me, creating film is a way of exploring the human condition—a way of making knowledge about what it means to be human. In this sense, filmmaking is a form of research unto itself.

I’m interested in telling the unlikely stories of unlikely (and often underdog) protagonists.

I always hope to eschew melodrama in favor of finding the drama and poetry in even the most seemingly mundane of places.

I’m curious to explore how we, as individuals, find our own personal moments of meaning in spite of our frustrations and disappointments and often in the face of tragedy and loss. And I’m endlessly moved by our clumsy human struggles to connect.

I’m eager to push boundaries of conventional narrative structure when thematically purposeful, and to embrace them when appropriate.

I’m fascinated by a cinema where the pursuit of authenticity not only informs content, but also informs form, tone, telling, and pace, seeping into the structure and the unique DNA of a film. I believe that attempting to wedge authenticity—whether cultural, psychological, or societal—into standard, three-act templates, conventional film grammar, and socially realist tones can sometimes risk dishonoring the very authenticity that I’m aiming for.

In my own work, I’m always eager to enter into conversation with cinematic precedent and with the history of our medium. I’m fascinated by genre and am always keen to play with its tropes in order to subvert, reimagine, personalize, and poeticize them.

I’m always searching for the comedy within the drama and the drama within the comedy. I believe that humor is holy and strive to use it to honor the human condition and not to skewer it.

I want to make films that are conversations, not manifestos—that craft and court the right kinds of deliberate and purposeful ambiguity, the kind of messy ambiguity that turns a mirror on the audience, allowing each viewer to wittingly or unwittingly project themselves into those spaces and reveal their own truths via their interpretation.

But: beyond all of this, I believe ultimately in prioritizing the heart above the head in my own work. I believe that movies are, at their best, empathy machines, and that it’s through cultivating our earnestness as storytellers—our grasping for universality through odd specificity and our dogged pursuit of emotional truth—that we’re able to move and engage audiences—especially in place of less traditional narrative rewards—and to ultimately keep them interested and invested in ever bolder cinematic experimentation.

Please share a vignette or a case study from your work and explain what lessons you draw from it.

My first feature, To Dust, had unlikely origins. The film is a science-centric story that puts Hasidic Jewish religion and folklore in conversation with grief and forensic taphonomy, and it was incubated, in large part, through support from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation. Having studied religion and the humanities as an undergraduate and having spent my twenties as a traveling singer-songwriter, I never imagined I’d one day be making movies about science. But, lo and behold, a few years on, I’m somehow working on yet another science-themed feature with developmental support from Sloan.

It turns out that stories about science and the scientific process are like creative catnip for me. In them, there are not only fascinating worlds and wealths of ideas to uncover, but also the metaphor of humanity’s impossible and relentless search for meaning; the frustration and awe that we feel when we reach the limits of our knowledge, both internal and external, and are forced to stare out at vast and complex unknowns; our valiant efforts to try to incrementally make sense of it all anyway; and, despite our repeated Sisyphean failures and inadequacies, to just keep pushing that rock up the hill.

Exploring human stories against the backdrop of science has consistently reminded me of the value in leaving my intellectual, artistic, and narrative comfort zones to put my mind in the most personally unlikely places. In doing so, I’ve come to trust that my thematic and stylistic fascinations/curiosities will inevitably follow me wherever I go—for better or worse—and to learn that leaving my home turf can create the potential for synergies and stories I never previously imagined.

In that way, I’ve begun to think of myself as a sort of interdisciplinary storyteller and have found myself keen on intense research and immersion as a part of my creative process, as well as on all of the collaborative opportunities that come with that work. Whether it’s traveling to forensic body farms in Tennessee or hanging out in Hasidic speakeasies in Brooklyn, this has become a key part of my creative process and my creative joy.

In that vein, the prospect of creating a long-term home at an academic institution like Rutgers, so interested in cross-pollination and collaboration across departments and fields, feels particularly kismet and inspiring.

How does your work as a researcher inform your teaching?

I’ve always taught alongside my own creative endeavors, and it’s a joy and a dream to now be teaching film at the university level. For me, teaching has always been a deeply symbiotic relationship, with the energy and inspiration flowing both ways. I truly hope my students feel the same. I do my best (and am always trying to cultivate new ways) to instill and inspire in them an exploration of their own authenticity, specificity, and diversity—not just in the stories they are telling, but also in the telling of their stories. I’m always interested in pushing students to reimagine the cinematic toolkit to these ends—to see that the tools of film language, craft, and structure, while conditioned with convention over time, are ultimately agnostic. I strive to help students master these tools only to then redefine, imbue, and utilize them with their own subjective meaning. I am encouraged by our industry’s growing, even if still quite limited, steps towards equity, diversity, inclusion, and representation, and I am inspired by Rutgers commitment to such. This, not only because of a desperate need for more professional and cultural parity in our field, but, as a film teacher, film maker and film lover, out of a deep belief that more diverse voices lead to more diverse storytelling and thereby the very evolution of the art form and the audience. My hope is that I’m creating an environment in my classroom that supports and encourages students to see themselves as part of this evolution. I additionally believe that the classroom is where we start to empower young filmmakers to challenge the more toxic aspects of the industry’s culture and to become agents of change in a field in which a shift toward more kind, ethical, and humane practices is long overdue.

What is one piece of advice that you would offer to a student considering a career as an artist or arts researcher today?

To be interested and curious in fields beyond film and most of all in people and in stories. To engage in life and the world fully, both through and alongside your creative work. To find your collaborators and kindred spirits and to hold them close.