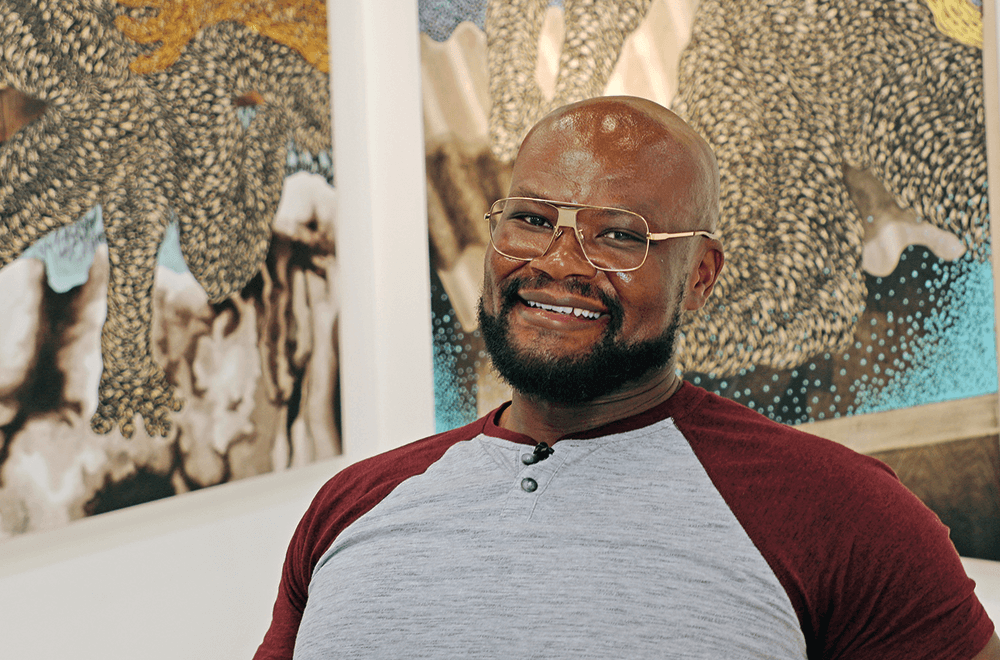

Photo credit: Alex Nunez and the Fountainhead Foundation

“It’s critical for young artists to feel supported. I’ve benefited from a great deal of support even before I had a clear vision of who or what I wanted to be. This laid the groundwork for the persistence I’ve relied on as a working artist and teacher.” – Didier William

Department of Art & Design’s Didier William joined the faculty in the fall as a professor of expanded print. In a recent New York Times profile on the Hatian-American artist, Laurel Graeber says that William’s works “incorporate collage, oil paint, and acrylic as well, making them as multifarious as the Afro-Caribbean diaspora itself.”

Much of your work is on wood, not canvas. What draws you to wood? What is satisfying about the act of carving?

The rigid and somewhat brittle surface of wood provides a material that has some resistance to my authorship, which I like. It’s an organic material, so inconsistencies and blemishes in the surface are natural, and I love that. It effects a kind of organic collaboration—a midway point between readymade and something fabricated.

Many of your works feature bodies or backgrounds covered with eyes. Your works seem to behold the viewer. Why has this emerged as a feature of your work?

For me, looking isn’t just about a stable, singular process, it’s something that takes place in the present moment between the bodies in my paintings and the curious viewer. The eye motif developed out of an urge to make this process physical. It grew out of an attempt to trace the process of looking and bearing witness. The repeated eye forms work to make physical the otherwise unseen circuitry of looking and being looked at. Here I’m very much thinking about Michel Rolph Truillot. His text on the function of historical silences, Silencing the Past, has been an important one for me. In it he argues, “Historical representations—be they books, commercial exhibits, or public commemorations, cannot be conceived only as vehicles for the transmission of knowledge, they must also establish some relation to that knowledge.” This greatly resonates with me, particularly in terms of how I think about the body and representations of human form.

How has geography shaped your work? You were born in Haiti and then moved to Miami as a child. Now you live in Philadelphia and teach in New Brunswick. How do these places seep into your work, if at all?

Probably most directly, the geography of the places I’ve lived have influenced my aesthetics and the aesthetics of the different places I’ve lived continue to influence my work. I immediately think of color with this question, and I think it’s hard not to think about South Florida, where I grew up, as one of the primary sites that helped build my relationship to a kind of cultural aesthetic that I associate with a particularly diasporic experience. As you might know, South Florida is home to the largest Haitian population outside of the country of Haiti. Additionally, it is also home to many others across the Latin American diaspora. In this remaking and re-mapping of home, I think a very unique and peculiar aesthetic is built, wherein color, surface, and texture are projected onto everything from textiles, to architecture, the landscape, to the food, even the language. And so there is a kind of rich tapestry, an evolving grit that is characteristic of South Florida’s material culture. It’s not uncommon in South Florida to see brilliantly colored homes with terra-cotta rooftops, and bright green porches. The South Florida Sun also illuminates everything with a piercing, blinding luminescence. These are the very much the colors that I source in my paintings.

In my work I also try to take what are thought of as usual or typical associations with color and re-distribute them. Bodies and landscapes can exchange scale and surface. I try to take colors we would associate with architecture and bring them into the body, colors we would associate with sky and bring them into the ground, and vice-versa. In this kind of reassessment of the picture plane I’m attempting to create an alternative space in which the viewer can certainly find familiarity, but they’re intentionally slowed down. Even when things are sort of explicitly familiar, I try to disassociate them from the usual cultural symbols to which they are attached.

Additionally, I think I must also say that my mom is a chef. She has a Haitian restaurant in Miramar, Florida, and so I grew up constantly surrounded by delicious Haitian food and Haitian cooking (which if you know anything about it, is really spicy and colorful and flavorful with rich ingredients. Haitian food comprises an incredibly layered palette), and I often like to say that the way that I think about painting and art is very much the way that my mom thinks about cooking and food…. My associations and relationships to color in the print shop have always been analogous to food. There’s a beautiful synchronicity for me that exist between the alchemy of printmaking and the alchemy of cooking.

You’ve mentioned a teacher who believed in you as an artist when you were very young. Can you talk about the significance of that faith—and your parents’ devotion to your education as an artist?

It’s critical for young artists to feel supported. I’ve benefited from a great deal of support even before I had a clear vision of who or what I wanted to be. This laid the groundwork for the persistence I’ve relied on as a working artist and teacher. My parents’ support not only reminded me that I was loved and cared for, but that what I had to say was important and that I deserved to be heard. We owe young artists this affirmation.

How does the act of teaching, and the relationship with young artists in your classes, inform your art-making?

I don’t think teaching offers a direct influence on my practice. However, teaching is itself a practice of turning complex thoughts and ideas into a system of elastic codes and languages. I compare this elasticity to a kind of athleticism that requires stamina, curiosity, and patience, all of which are also helpful in my own studio.

Learn more about Didier William